The Popularity of Things That Are Wrong

Why data-driven too often means ethics-free

People are getting very excited about Trump’s favorability numbers, and the growing support for abolishing ICE. I’m excited that they’re excited.

And I regard these trend lines as Good Signs. But we shouldn’t get too excited about them.

Professional Partisans v. Their Voters

As many of you hopefully know because you subscribe to G. Elliott Morris (you’d better!), he’s been tracking the unraveling of Trump’s 2024 coalition. Recent polling makes it pretty clear that the people who were new to his coalition, the people that so many professional Democrats have been freaking out about — younger voters, voters of color, and new/infrequent voters — are falling out of “love” fast. He of course makes the argument that Trump’s voters were not so much re-aligning as de-aligning.

Plenty of polls and pollsters are watching this “coalition” unravel. But here I feel I must once again make the distinction: voters are not the same as professional partisans.

And if you want evidence of a de-alignment of Trump-touting professional Republicans, the evidence is… let’s say highly contingent.

Lindsay Cormack’s excellent newsletter has been tracking Congressional emails to constituents. Up until the events of this past weekend, the de-alignment was not in evidence among elected Republicans. “Republican e-newsletters present a unified, celebratory account of presidential success,” she wrote. It’s worth a look to see how members of Congress are showcasing pictures of themselves with Trump, touting his victories, and generally cheerleading an unpopular president (but, hey, at least he’s their unpopular president).

Obviously, this week we have seen more blowback from the depraved response of the administration to the murder of Alex Pretti. Over the weekend and into this week, several members of the GOP caucus have called for accountability of one kind or another.

But these moments are highly elastic. Alliances can snap back, or they can be stretched until they break. The question of which outcome is more likely is down to a question of force. Who is going to keep doing the stretching? Who is going to release the tension and allow it to snap back?

Observe the data, and let it go

As the news of Pretti’s murder was unfolding, clearly a lot of surveys, focus groups, and depth interviews were going on, and a lot of strategists were putting together a lot of bullet points for a lot of professional Democrats.

According to NBC News, Chuck Schumer, my senator, was advising the caucus that the position to take was “restrain, reform and restrict ICE.”

At around the same time, John Della Volpe was writing in his newsletter based on some interviews he apparently did over the weekend,

Choose reform and oversight over extremes. Gen Z is not calling for abolition — and they’re not defending the status quo. They want lawful enforcement that is humane, transparent, and constitutional. Their message to Democrats is simple: don’t swing between “defund” and “fully fund.” Fix what’s broken.

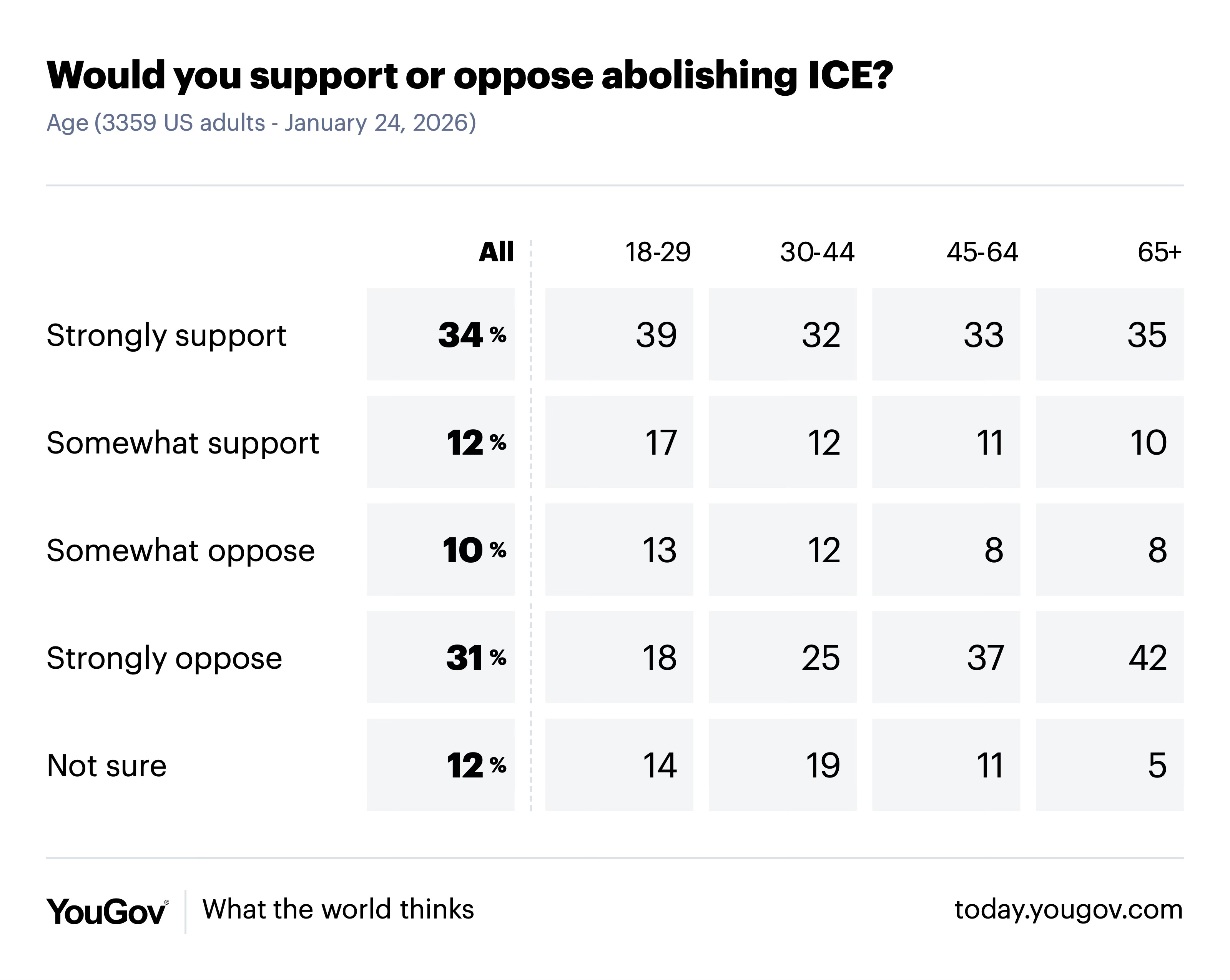

Meanwhile, YouGov asked people whether they supported abolishing ICE, and here’s what they found:

56% of Gen Z adults do at least somewhat support abolition. By contrast, 31% at least somewhat oppose abolition. The upshot is this: Gen Z is the age cohort most likely not only to support abolition, they are the least likely to oppose it. The net favorability for the “abolish ICE” position among these voters is +25.

If you’re Democrats worrying about young Democratic-leaning voters turning away from your party, I’d consider, you know, listening to them.

Gratify this half, astound the other half

This clash of data points (not much of a clash, tbh, but let’s pretend) illustrates the essential bankruptcy of the popularist position. “Doing what’s popular” depends on who you ask, when, and how.

But worse, “doing what’s popular” absolves you, as a leader or aspiring leader, from ever having to consider the question of what is right, and what is wrong.

That a lot of people will say on a survey that they think that immigration is a problem and we need to protect our borders does not, in fact, mean that Operation Metro Blitz was right.

And the timidity, the hesitation, the waiting for a pollster to give you a lame alliteration — that is what voters mean when they tell you they want you to mean what you say, and do what you say.

But the thing about leadership is you don’t wait for your followers to tell you what’s right. If you’re waiting for American voters to dwell in virtue, you might be waiting awhile. Or you could, you know, try to persuade them.

Let’s look at some things the voters were wrong about.

People didn’t like the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.

- In 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr. had a net favorability rating of +4 points. 1 in 4 Americans surveyed held highly unfavorable views of him. By 1966 he had a net favorability rating of -30 points. In early 1968, the year he was assassinated, a Harris Poll found his disapproval rating was 75%.After his assassination, 31% said that he had “brought it on himself.”

People supported the war in Vietnam, until they didn’t

- It only took 19,000 US deaths in Vietnam to start to convince people the war was a bad idea. From August 1965 until January 1973, Gallup regularly asked the following question: “In view of the developments since we entered the fighting in Vietnam, do you think the U.S. made a mistake sending troops to fight in Vietnam?” In October 1967, more Americans thought it was a mistake than didn’t for the first time; in August the following year, the percentage who thought it was a mistake nudged up to a majority view — 51% thought the decision was a mistake. In 1968 alone, nearly 17,000 more would be killed, bringing the total US death toll to about 36,000.

People didn’t support anti-war protesters, though

- In May 1970, a day after 4 students were killed and 9 others wounded at a protest on the campus of Kent State University by National Guardsmen brought in by the Governor of Ohio precisely to put down such protests, Gallup asked Americans who was to blame. 58% of Americans surveyed blamed the students.

People learned to love the post-9/11 security state

- The USA-Patriot Act was more popular 7 years after it passed than it was in 2004; by 2011, even Democrats belief that it was a necessary tool to fight terrorism had grown by 10 points, with 35% support. (By contrast, Republican support had dropped by 8 points, no doubt because these tools were now being wielded by a Democrat.)

- The Homeland Security Act, which created the Department of Homeland Security, was broadly popular. 73% of Americans supported the Act’s passage, and the creation of this department — though just over half felt it wasn’t really urgent (they didn’t agree with then-President Bush that it needed to be created before the anniversary of the 9/11 attacks).

- In June of 2002, a Time/CNN/Harris Interactive poll asked Americans if Congress should pass legislation to create the department; 69% said yes, including 68% of Democrats, 70% of Independents, and 72% of Republicans. When asked if the creation of a DHS would lead to abuses of power on the part of the authorities, 43% said it would, 47% said it wouldn’t and 10% weren’t sure. 57% thought it would cost too much. 52% thought it would create too much bureaucracy. But 71% thought it would make the US safer from terrorist attacks; by contrast, only 58% thought it would make them feel more secure, personally.

Torture is bad, except when we do it

- Between 2004 and 2015, various pollsters asked Americans whether “the use of torture against suspected terrorists in order to gain important information can be justified”. They found growing support for the use of torture, from 43% on average saying it can be justified in 2004, to 51% saying so in 2015. In 2004, photos from Abu Ghraib supposedly shocked the nation — but 60% said it was abuse, not torture (just 29% said it was torture). Over a six year period, from 2004 to 2010, agreement with the statement “Rules against torture should be maintained because torture is morally wrong and weakening these rules may lead to the torture of US soldiers who are held prisoner abroad” fell 12 points.

Voters look to elites to help them form opinions. Elites opposed the Civil Rights Movement, supported the war in Vietnam, and the war in Iraq and Afghanistan, wanted sweeping police powers, and wanted you to believe that the “international war on terror” had rendered the Geneva Conventions “quaint”. Over time, those preferences gained quite a bit of ground — because no other elites had the guts to oppose them.

Just because too many voters like it doesn’t mean you have to

As of 3 days ago, after Alex Pretti’s murder, according to YouGov:

- 46% of adults support abolishing ICE

- 57% disapprove of the way ICE is performing its job, with about half strongly disapproving.

But:

- About half of Republicans say ICE is using just the right amount of force.

- 44% of Republicans say the shooting of Alex Pretti was justified.

- In a CNN poll taken after the murder of Renee Good, 56% of Republicans felt the use of force against Renee Good was an appropriate use of force.

- Likewise, 67% of them think that ICE enforcement actions are making cities safer.

Immigration is popular/unpopular

Let’s just take Americans’ views on immigration over time, since supposedly that’s what all this is about.

Support for more restriction on immigration have long been broadly popular. In the US, in 2004, just under half of Americans “completely agreed” with the statement, “We should restrict and control entry of people into our country more than we do now.”

In 2006, just after an immigration enforcement bill was passed the prior winter, Pew looked at an array of polling to see where public opinion was. An NBC/Wall Street Journal poll conducted that April found that opinion was evenly divided on the question, “Would you say that: immigration helps the United States more than it hurts it, or immigration hurts the United States more than it helps it?”. 45% said it hurts more than it helps and 45% said it helps more than it hurts.

A Pew poll conducted in February of that year found that 52% thought immigrants were a burden on the country, “because they take our jobs, housing and health care.” That poll also found that 40% of respondents thought immigration should be decreased and only 17% thought it should be increased. Large majorities thought illegal immigration was a serious problem. Of course, most did not think they should be deported, and (almost perversely) Democrats were generally seen as better on immigration policy than Republicans.

By September 2009, 55% of Americans in a Pew survey said there were “strong” or “very strong” conflicts between immigrants and people born in the US, much more than other divides on race, age, and class.

The truth is that the public has long held internally complicated views about immigration. By 2013, people were broadly in favor of letting undocumented immigrants remain in the US, but also believed immigrants were a “drain on government services.” Tea Party Republicans were driving the most anti-immigrant views — non-Tea Party GOP voters agreed with the statement “Most undocumented immigrants are hard workers who should have the opportunity to improve their lives” by 20 points more than Tea Party GOP voters did.1

In research conducted in October of 2025, Pew Research found that 53% out of American say that when it comes to deporting immigrants who are living in the US illegally, the Trump administration is doing too much — that’s up 9 points in six months. Republicans still broadly think the administration is doing about the right amount, but the number who agree with the majority that they’re doing too much also grew by 7 points in six months.

Opinions aren’t static

I say this all the time to clients: a brand is a story we all know.

I say this, too: we don’t do research so you can chase customers around the field; we do research to understand where they’re headed, whether we can redirect them, and if we can’t, what we should be prepared to do when we meet them there.

Opinions change.

And here I want to recommend a few things to anybody who might make decisions about strategy here:

- Stop looking at snapshots, look at trends. See how opinion is changing. G. Elliott Morris is doing this for you, so just … subscribe already.

- When opinion starts to move — people change their opinions, or start saying “don’t know/not sure” more — it’s time to get in the arena. Opinions are up for grabs, the concrete sort of “un-sets”, and can be molded into new forms.

- But of course, if you want to shape public opinion, rather than chasing it, you should know what you think is right. You should say that.

- And once you’ve said it, stand on business. Show up in solidarity with the people whose side you are on, propose legislation, convene hearings, call witnesses, vote in line with what you said you think is right.

Your first move in a moment of tumult is not to ask a pollster what voters think, it’s to ask yourself what you think. What kind of world do you want to be living in ten, twenty, thirty years from now? If you know what kind of world that is, then you make decisions today that comport with that vision.

I spoke with Amanda Litman for the show, and she made some truly excellent points, but the two that I keep thinking about are these:

- When you focus on the long term, and spend more effort tracking progress on your strategy than measurement of your tactics, the short term often takes care of itself.

- Referencing Lauren Egan’s piece in The Bulwark, Amanda also said, “Moderates don’t excite a ton of passion. There aren’t a ton of moderate candidates for whom you’re like, “Yes, better things are only kind of possible! What an engaging rallying cry, what a vision for let’s nip around the edges of the status quo”!” In this moment, a time of monsters, per Gramsci, why not battle the monsters and midwife the new world you want, instead of standing by and watching it struggle to be born?

We can blame voters for many things — for their inanity, their disinterest, their laziness, their mistrust, their gullibility, their political fandoms, and their fickleness. But voters could just as easily describe their elected officials in the same terms. Who are the lions, and who are the donkeys, and who is doing the leading? Well, that remains an open question.

So let’s return to my opening metaphor: the elastic band ready to snap back, or break. The question of which direction it will go depends on who is pulling on the band. If Democrats decide to play it cautious, to nip around the edges of the status quo with inane, alliterative taglines nobody will ever remember, then the band will snap back, and Americans will soothe themselves with the misremembered adage about bad apples.

If Democrats decide to play it for the future, with passion, they can break this elastic band that’s been holding us, squeezing our positions on immigration until violence is a viable option.

But to do that, they should not just think about what’s popular, but about what is right.

Democrats were evenly split on the question of whether undocumented immigrants being allowed to remain in the country would be a “drain on government services”, but conservative and moderate Democrats were much more likely to say so - by 19 points. ↩