Why does all this ambition & abundance seem so... small?

A few half-formed thoughts on what I suspect is getting in the way of leadership.

I wonder if you’ve had this experience. Someone tells you about something they think is brilliant, amazing, innovative, essential. And you … just don’t get it. Like, they can explain it over and over and you understand the words, but for some reason, it doesn’t make sense.

There are a pair of books out right now that I am very curious about, but as I am in a perpetual reading backlog, I have not yet read them. However, I voraciously consume (with time that would probably be better spent actually reading the books on my nightstand) any interview I can find with their authors.

One book is Abundance by Derek Thompson and Ezra Klein. The other is Moral Ambition by Rutger Bregman.

The thing that both books call for might simply be called “leadership”.

But they also show how difficult leadership really is… or rather, how hard it is to write an Ideas Book about leadership that can not solve for the greatest impediments to leadership, at least in America: maximizing shareholder value in the private sector and doing what’s popular in the public sector.

But even that isn’t quite going deep enough.

The chief hindrance of leadership is (might be?) an anti-empirical, axiomatic, mathematicalized, mechanistic view of human society and behavior.

Leaders don’t do leadership, they do algebra.

Just listen to this from Abby Innes, who I think has some extremely interesting ideas.

We do have an aristocracy, actually

I feel like now I’m have to tell you one way that Marx was wrong1 — he separated the classes into two parts: the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. The bourgeoisie owns all the capital and the means of production (and the levers of government), and the proletariat doesn’t.

But this isn’t quite right. It’s more layered than that, and it utterly ignores an aristocracy (probably because he was thinking about what his battle would be after the aristocracy was toppled, lol). The aristocracy owns the capital and the means of production; the bourgeoisie simply operates it on their behalf. Now, if we must, we can stipulate that a per se aristocracy does not exist in America, but I think we can also stipulate that a de facto aristocracy most certainly does exist. That we permit some people to rise out of the middle classes to become aristocrats distinguishes modern time from medieval ones, but it doesn’t seem like something to feel too proud of, to be honest.

Still, by trying to evade the reality of the aristocracy, we definitely spend far too much time thinking about the people at the top of the middle class, and how they fail to lead, and not enough time thinking about how a class system that can exist within — or alongside — democracy and market capitalism, seriously limits the amount of leadership the top of the middle class can ever exert.

Maximizing Shareholder Value

If you work in the private sector, especially for a publicly traded company, but really for any company (even one with only one shareholder), then this is what you are ultimately accountable to.

And where does this idea come from? Look, businesses have always existed to make money. But businesses have also had many reasons for wanting to make that money, and many different levels of ambition, and many different approaches to making money. Peter Drucker famously said that the purpose of a business was to create a customer. And because that is its true purpose, “any business enterprise has two – and only these two – basic functions: marketing and innovation.” In other words, he believed businesses were about value creation. He also thought that businesses could drive positive social outcomes.

For Milton Friedman, this was woke ideology.

“WHEN I hear businessmen speak eloquently about the “social responsibilities of business in a free‐enterprise system,” I am reminded of the wonderful line about the Frenchman who discovered at, the age of 70 that he had been speaking prose all his life. The businessmen believe that they are defending free enterprise when they declaim that business is not concerned “merely” with profit but also with promoting desirable “social” ends; that business has a “social conscience” and takes seriously its responsibilities for providing employment, eliminating discrimination, avoiding pollution and whatever else may be the catchwords of the contemporary crop of reformers. In fact they are—or would be if they or any one else took them seriously— preaching pure and unadulterated socialism. Businessmen who talk this way are unwitting puppets of the intellectual forces that have been undermining the basis of a free society these past decades.”

He did not only introduce the prime directive of maximizing shareholder value, he created the conceit that any other directive was laughably stupid, naive, or rife with the sinister motivations of the socialist.

Remarkable, isn’t it, that his point of view arises only in the 1970s, and was subsequently taught by Michael Jensen at Harvard Business School - specifically saying that a CEO’s interests and shareholders’ interests should be aligned through compensation of the CEO. The idea is about as old as I am, and we act like it was handed down to us from God.

Since then, CEO compensation shot through the roof — an amazing, billion-dollar carrot. But every carrot seems to come bundled with a stick — and that stick was short-termism. CEOs not only were incentivized to align with whatever increased the value of a company’s stock price, they were incentivized to do whatever it took to put money in shareholders’ pockets. Failure to do so, as the recent resignation of the UnitedHealth CEO indicates, means certain punishment from shareholders. They will sue you for being “too nice” to the customer.

There are a certainly many billionaires who are CEOs. But most CEOs aren’t billionaires, and most of CEO compensation is in stock, not cash.

What’s my point? CEOs aren’t in charge. Shareholders are. And what they want is simple: Line Go Up.

But if that’s what they want, and that’s all they want, then you, as a leader, are severely restrained. You mustn’t pursue a policy or product that creates a customer by creating value but limits profitability in any way. You mustn’t make long term investments in future revenue streams that undercut the profitability of current revenue-generation. When sales decline, cut operating costs (e.g., employees, marketing, R&D). When market prices decline because the general economic climate is poor, cut operating costs. When supply chains are disrupted or inflation goes up, raise prices. All gains are privatized - paid out to shareholders; all losses are socialized - paid for by customers and the workforce.

If these are the rules of the game, then ambition in these leadership roles is small. And as you move across the executive leadership team and down the org chart, the ambition gets smaller and smaller until it is almost ridiculous. Executives make up KPIs they know they can both measure and game, and report those credulously to their C-Suite, who report it to their Boards, who ignore everything except how you performed against expectations and whether Line Go Up. The very last thing any CEO wants to do is disappoint on the direction of the line - because then and only then will shareholders take an interest in those KPIs. But if Line Go Up, then congratulations on your CAC and ROAS numbers, those look great, too.

When Rutger Bregman talks about moral ambition in his columns and interview appearances, he often has to admit (though he does so in a way that suggests he is definitely judging you for being so provincial) that it’s difficult to exercise moral ambition when you have a mortgage and two kids. His examples of moral ambition are often from decades or centuries ago. The people he holds up often relied on some combination of academia, philanthropy, and lower living standards. They rely on a time before Milton Friedman and Michael Jensen and healthcare CEOs who are caught between fear of getting shot by angry customers and fear of getting fired by angry shareholders.

When I talk to business leaders who want to create the conditions of a more moral approach to leadership, I believe that they believe what they are saying2. I believe that they want more grounded leaders who are less reactive and more comfortable navigating uncertainty, who act with integrity, and do what’s right3. And I applaud them for advocating in this way, because it’s far, far better than not doing so. And in any case, if you have more than, let’s say, $5 million in cash, I think there’s frankly no excuse for you to be acting otherwise except that your ambition is about more money and maintaining status. And neither of those things come from within. You have decided to serve the aristocracy, in the hopes of one day entering it.

But if your household is only making $150,000 or $250,000, or even $500,000 a year in salary before taxes, and the shares you got as part of your compensation package you can’t afford to exercise? I’m not sure why you would conclude, in your capacity as a director or VP or some C-suite role in a mid-sized firm, that you can afford to buck the shareholders, or do something to your company’s EBITDA that will make your firm less attractive to the private equity firm the board hopes to sell to.

In a way this is just a kind of small fantasy of the top of the middle class, the people who think they are one private jet away from the aristocracy. They believe that they can self-help their way to a moral authority that transcends the question of net worth. But here’s the rub:

The way you play the game doesn’t change the rules of the game.

Moral ambition is — from what I’ve heard so far — just not ambitious enough. Moral ambition would strike at changing the rules of the game. Because it is the rules of the game, and not just the players of the game, that create immoral or amoral processes and outcomes. You’re not going to box breathe your way to a more equitable oligarchy.

And so in the spirit of Abby Innes, I’m going to suggest that one thing to call for is not an obliteration of the concept of maximizing shareholder value, but a more empirical, less mechanistic, more pluralistic set of rules and values. Let it be only one of many goals a company might have. Let other rules and values include the notion that companies exist to create customers, and that they must spend money (aka “invest in”) creating that customer through innovation and customer service and yeah, even through marketing. Let there be other rules and rubrics we use, depending on the context, and let there be a role for long-term thinking and goal-setting, for making multiple plans that acknowledge contingency and uncertainty, and for creating accountability to more types of people than just the shareholders.

Of course, I’m not sure how you get there without regulations that require it. Because the de facto aristocracy — the money class — won’t go there willingly.

Popularism

When I listen to Derek Thompson or Ezra Klein talk about their abundance theory, all I can think about is the mythical median voter.

The median voter is a fiction, a thought experiment. It assumes that if you could identify the issues or policies that are the most broadly popular - the most popular among the most voters - you could chart them on a unipolar distribution curve, cut off the ends, leaving only the juicy center, and then design a political platform around the most popular issues and policies in that juicy center and hey presto! capture the most voters.

The median voter is core to the concept of popularism — which is essentially a political strategy that can be summed up as “Do what’s popular”. Just as with shareholders, political donors, strategists and commentators want to see Line Go Up. But this line isn’t the stock market4 — it’s the polling average, and maybe the quarterly fundraising report.

The median voter is often described as a moderate or an independent; but we know that the “moderate” political position is at best incoherent — they are left on some things, right on other things, and indifferent about most things. We know that independents are very often synonymous with so-called “low information” voters — people who are just not very politically engaged, for a variety of reasons both good and not-so-good.

But Thompson and Klein are committed to an idea that whatever they prescribe in their book should be politically feasible. Thompson says so in an interview with Mehdi Hasan right here:

Here’s the quote:

“I believe in a singlepayer healthare system. I think that'd be the best path forward. I also want to be realistic, I also want to be politically realistic, right. I mean a good book has to be focused, a good book has to understand what is the core argument that it's trying to make. We can't make every single argument. We're not talking about every single thing that could possibly be good in any political future. We're trying to make a very clear argument that in many ways the problems that Democrats face are the result of rules that they allow and the systems that they design, right. That is one very clear narrow argument of the book.

When it comes to socialized medicine I think there are of course — if you look at the case of Europe — arguments for having a singlepayer system that is allowed to negotiate prices with the private sector to drive down prices especially for the working and lower classes. There's a lot of good arguments for this. If you look at the politics of singlepayer healthcare, it's incredibly fraught and so rather than write a chapter about the fraught politics of introducing Medicare for all, right, which is a chapter of of a different book that that I could research and write and represent the arguments for I think very sincerely, I wanted to focus in my chapter on medical science on the ways in which the value of health care is not just determined by the card that you own it's determined by all the things that that card buys. So people like you, people like me, people throughout the Democratic party in the last few decades we've been very focused on universalizing healthcare, and again, I think that's a mitzvah. I want universal healthcare but sometimes in our emphasis on focusing on universal care we think a little bit less on what that universal care actually buys. And I think it's really important to have an invention agenda in America that focuses on all the medical technologies and the science that allows that health care card to buy more drugs that extend people's lives. So I want us to try much harder to build new medicines for diabetes and inflammation, dementia, Alzheimer's, all … certain kinds of cancers.”

I would like to know why they think that single-payer healthcare is politically fraught, but clearing away regulations — especially regulations that require notice and comment, which they seem to find distasteful — that inhibit building low-income and affordable housing, mass transit and high speed rail projects, nuclear and other alternative energy projects are not politically fraught (and how sure they are that it’s Democrats alone who weaponize them against necessary housing and infrastructure development).5

And I would like to know where they think the political support for this agenda will come from. When these policies meet the voters, will it still be a popularist agenda?

Here is the trouble with the way these popularist, supply-side, abundance centrists think about the world (and yes, I’m mashing it all together, because I sense that they are all part of the same intellectual tribe).

They start from a kind of mechanistic, axiomatic, mathematicalized view of the world. They believe that the thought experiments are just as good as empirical reality. They look at data correlations and normal distribution curves and see beauty and truth. And these beliefs become the rules of the game. They become the rules by becoming the frames of fundraising, polling, messaging, and political coverage. Agree with Major Donor A on these policies, get $50 million. Agree with Centrist Columnist B and get a lot of media hits and attaboys from the consultant class. Bizarrely, both are valuable currency.

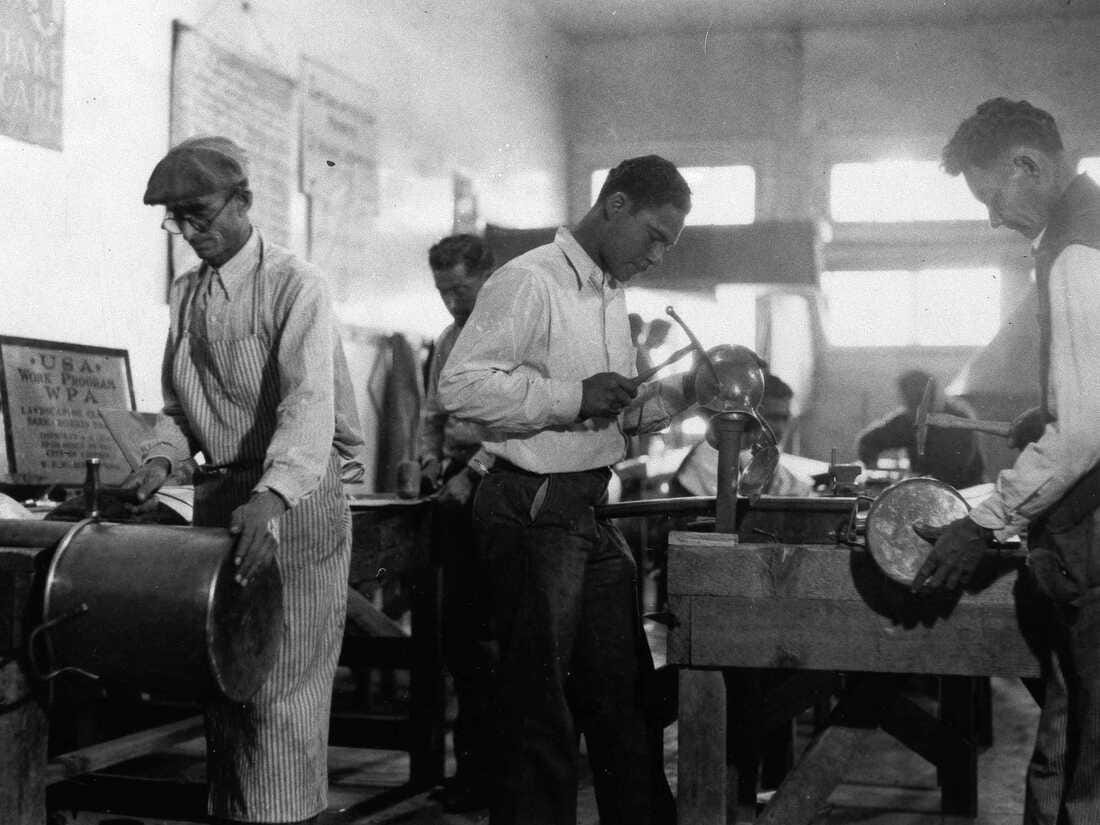

But despite what the Abundance Boys seem to believe (an Operation Warp Speed in every state!), their agenda sounds a lot like maximizing shareholder value to me. They say they want to deregulate government, but the effect is chiefly to deregulate the private sector. They want fewer checks and reviews and standards to apply to contracts that will be awarded not to WPA employees but to construction and transit and energy and drug companies. And those companies are responsible — and responsive — not to government, but to their shareholders. The abundance in the abundance agenda will inexorably accrue to the benefit of these companies and their shareholders.6

And this is where we have to admit that the candidates, like the CEOs, are not in charge (and neither are the parties). The strategists and the pollsters and the parties and the politicians are the bourgeoisie — the managers of the capital and the means of production. Meanwhile, the shareholders aren’t the voters — we’re the customers and the employees.

So who are the shareholders in the public sector?

Same as the shareholders in the private sector.

The question I want to put to all of these people — the C-Suite leaders and the people shilling books about leadership and abundance — is this:

Is it possible to have both a value-creating market capitalism and a representative democracy when we have a de facto aristocracy driven by a singular desire for Line Go Up? And if they believe it is possible, can they explain how?

Finally I want to say this. I think Abundance is an appeal to the top of the bourgeoisie. I think Moral Ambition is too. And I think the Bulwarkian tendency to appeal to “political elites” as needing to stand up to authoritarianism — university presidents, partners of white shoe law firms, CEOs — is likewise an appeal to the top of the bourgeoisie.

But they can not be shamed by their colleagues; the petit bourgeoisie has petit ambitions, too, and will usually prefer to climb over the bodies of their fallen comrades than stand in solidarity with them. So the only thing that motivates the top of the bourgeoisie more than their dreams of joining the money class by working their will, is the discontent of the working classes (inclusive of the lower tiers of the bourgeoisie, but dominated by workers).

I’m not totally sure this line of thought is coherent, so drop me a line if you have any challenges, questions, or more things for me to think about and learn.

Great news! I’m not a Marxist.

HONESTLY I think (I hope!) these folks have their hearts in the right place, and the extent to which I find their solutions wanting is not really an indictment of them personally. I think their solutions are necessary, but not sufficient, to address the obstacles to moral leadership and ambition.

I have a guest on next week to talk about these very themes!

Sometimes it’s the stock market, though.

I would also like to know why they like centrally-planned economies and winner-take-all low-tax/low-service states so much, but I guess I’ll have to wait for someone else to ask them.

But perhaps most importantly, I would like to understand where the money will come from after this administration is done stripping the government for parts and starving it of resources, and spending way beyond their Congressionally allocated means on things the Congress did not authorize. They are pursuing a strategy of break it, shrink it, and bankrupt it as fast as you can. Will anyone believe there is abundance to spend in 2028?

This seems particularly perilous as a foundational idea — in many respects this election was about how little people trust government, corporations, the money class and the money managers. But for Abundance to work, we’d have to trust… all of them?