Political Market Making

The key to matching voters with ideas is mobilization

In poll after poll going into the June NYC Democratic mayoral primary election, Cuomo appeared to have at least a 10-point lead over Mamdani. There has been a growing narrative that polling is off as compared to the final results when it underestimates the actual vote on the right. But this election showed, that it can just as easily underestimate the actual vote on the left. Why?

We do not know who the electorate will be.

That’s it. Your polls are off? Focus on sample size, or whether people who take surveys are weird, or weights, or expressive responding, or social desirability bias, or any number of things people prefer to talk about because they are all, theoretically fixable.

But there is one thing that’s not truly fixable. And that is that the electorate is something that doesn’t exist until it does. Nobody knows how to predict with certainty who the electorate will be, or how big it will be, and as a result, it’s impossible to predict with certainty who the winner of the most votes among that electorate will be.

Why does it even matter?

I have to confess, I struggle with this question. I ask it of almost every pollster I’ve interviewed. Some version of, “What if we just didn’t make predictions?”

And that question just … doesn’t really compute. Why wouldn’t we make predictions?

And of course we do want someone to make predictions. Audiences want to know who is going to win. Campaigns want to know where to spend money. Candidates want to know whether to get in or drop out. Degens want to know how to place their bets. Newsrooms want to know which candidates, and issues, to cover.

Predictions - forecasts, if you prefer - are always for one purpose: planning.

If you know where things are headed, you have to time to plan what you’re going to do when you get there.

Voters apparently want to vote for the winner, don’t want to waste time getting to know candidates that don’t stand a chance. Campaigns want to concentrate their cash in the places with the most impact. Candidates want to save face. Newsrooms want to assign reporters and time/inches/pixels to the stories that will get the most engagement. (Degens are gonna degen, I don’t know what else to tell you.)

But when you don’t know who the electorate is going to be, and you “have to” engage in forecasting because you have to engage in forecasting… then you set yourself up to be wrong, and for everyone else to make the wrong plans.

Pick the winner, but root for the underdog

Even though voters, it seems, like to know who the winner is, it’s not necessarily because all voters are inclined to vote for “winners”. Voters like underdogs, too.

Years ago, I worked on a new audience segmentation study for NASCAR. I attended race weekends, and hung out with people while they watched races on TV. Sitting in the stands at Bristol, Tennessee (the fastest half mile in NASCAR), the fumes filling my head, the roar of the engines rattling my organs, I got a lesson in why people love to watch the sport.

Fans know who the favorite is. The favorite may or may not be “their” driver though. Everybody’s got their driver, and most fans prefer the drivers who win. But sometimes, pretty early in a race, you know exactly who is most likely to win. And so watching the known winner make hundreds of left turns often times ceases to be what the true fans care about.

They start looking at the middle of the pack. That’s where the action is. The drivers who are actually competing to get into position, to get the points, to move ahead in what used to be called The Chase (now, the playoffs, boo). And in that pack, if there are no drivers you love, well - you root for the underdog. The driver who only has one car, who’s never won a race, who doesn’t have many big sponsors, who won’t win today, but might win someday.

Some voters, I suspect, do this too. When it looks like a foregone conclusion - when there is an obvious frontrunner, who is way ahead in the polls, and way ahead in the fundraising, and all the party elites have endorsed him and all the newspapers are simply assuming he’s going to win… some voters decide to look further down the list, see who’s actually showing some mettle, some drive, some talent - and who actually wants it bad enough to just go for it without playing it safe.

But there isn’t always a candidate like that.

Some candidates are market makers

A market maker is an intermediary who is able to match buyers and sellers. They profit when the bid on an asset from a buyer is higher than the ask on the asset from the seller.

In this analogy, I want you to think of candidates as market makers. They match voters with positions and policies. “Frontrunners” have volume on their side, so the bid doesn’t have to be that much higher than the ask. People have to want the policies/positions/politician just enough to go vote for him. But “underdogs” - they don’t have a pre-set volume (a base) on their side. So for them, the bid has to be quite a bit higher than the ask. People have to want the policies/positions/politician enough to do more than vote for him. They have to mobilize.

There aren’t a lot of candidates who get bigger bid-ask spreads.

[Yes, I am torturing this metaphor, you will find all sorts of weaknesses in it if you want to, but just roll with me for a moment.]

The frontrunners, small bid-ask spread market makers, are easy to model, because they are the most common type of winner in elections. More often than not, winners start out with a larger base of support, greater name recognition, more money, and … less ambitious plans. They are neither meant to rock the boat, nor rock the vote. They’re just trying to get past the post.

But the underdog, big bid-ask spread market makers are nearly impossible to model. Often because they’ve never run for office before, or never run for this specific office. They do not start off with big bases of support, they do not have great name recognition, they do not have a lot of money. But a true underdog market maker of this type - she’s got big plans. To win she has to both rock the boat and rock the vote. She needs to win decisively, especially if she’s going to have any hope of delivering value for the bid.

If you’re trying to pick which market maker is going to dominate, how do you produce a forecast that accounts for the underdog?

There is more than one way to model the electorate

The standard-ish way to model the electorate is to look at the last electorate. Most polls that are attempting to forecast the outcome of an election (which, I know, I know, how can it possibly be both a snapshot in time and a forecast, it’s stupid, I agree, but we live with it), screen their respondents by registration status, and whether they have voted previously in similar elections. The baseline assumption is that there is a certain amount of stability in the makeup of the electorate because for many people, voting is a habit.

But we learned in 2008, and 2016, and in some sense in 2024, that there are people who haven’t formed the habit yet who can be enticed to start; people who don’t vote unless they’re inspired can be inspired; people who usually vote for some other kind of candidate can be persuaded to switch. Similarly, people can be demotivated - can choose the perennial third party in our two-party system, “The Couch”.1 Some group of voters who usually can vote may decide they don’t like their choices. So they choose to not vote. And in the words of my sophomore year high school Advanced English teacher, Mr. Morton, “by not choosing, you have chosen.”

Public Policy Polling published a press release this week, which included this:

PPP saw Zohran Mamdani’s first place finish coming before anyone else did for one simple reason: we polled the 2025 electorate instead of the 2021 electorate.

Usually when polling a primary election pollsters start out with a list of voters who have participated in similar elections in the past.

It was clear in this election though that Mamdani was building a movement that was going to bring a lot of people into the process that had never voted in a city election before. So we made a conscious decision not to require people we polled to have voted in 2021. If they said they were going to vote on our screening question that was good enough.

Tens of thousands of people voted in their first Mayoral election this year. We found those who didn’t vote in 2021 breaking 63-18 for Mamdani. We included them in our poll.

Beyond that this election brought serious demographic change to the electorate. The voters were much younger.

Pollsters know that most of the time it’s very hard to get young people to answer a poll and you often have to weight them up. There was so much enthusiasm from young voters in our raw data that we found 37% of likely voters were under 45 unweighted. Our poll correctly found a much different electorate than usually votes in primary elections. When all the final turnout numbers come in, it will probably turn out we should have projected an even younger electorate.

There were so many factors that could have steered a pollster to model a different electorate than the 2021 NYC election. Let’s just go through some of them:

2021 was still peak Covid. I know people like to pretend otherwise, but the vaccine rollout began at the start of 2021. Today, people are doing the absolute most to memory-hole Covid.

It was also the beginning of the Biden presidency. He had not yet pulled out of Afghanistan. Trump was no longer on the ballot. Today Trump is back on everyone’s ballot.

Adams won after 8 instant run-offs with 31% of the first place ballots. Mamdani won 44% in the first round and is now uncontested.

Adams can not be called a successful mayor. He’s been investigated, appealed to Trump for political cover, and has done little to materially improve New Yorkers lives.

Cuomo was in the midst of impeachment proceedings during the 2021 mayoral election. He resigned in August. His legacy did not age well, as scandals around his behavior in office, and his handling and coverup around nursing homes during Covid came back into the news with the incoming Trump II regime.

Democrats have become the owners of the gerontocracy problem because of The Debate, but also because of the age of their leadership. A 67 year old mayoral candidate was not going to turn out younger voters.

Democratic voters are growing tired of the party leadership. 62% in a recent Reuters/Ipsos poll said they thought there should be a change of leadership. The same study showed that Democratic voters think that the Party does not prioritize the same issues they do.

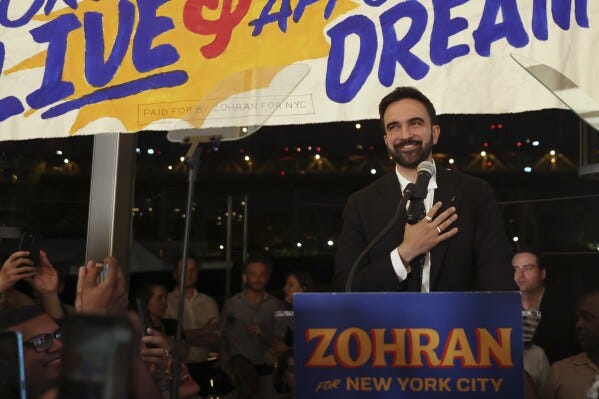

And then there was Mamdani. Young, socialist, Muslim, immigrant, former DJ/rapper Mamdani. Mamdani ran on “kitchen-table issues”. He identified the problem — the cost of living in NYC is too damned high. He put forward tangible-seeming solutions — free busses, rent freezes on rent controlled apartments, city-owned grocery stores, more housing development, raising the minimum wage, community safety programs, cracking down on deed theft and landlords who don’t keep their buildings up to code, taxing the 1% by 1% more, marrying a modestly socialist program with elements of the so-called Abundance Agenda.

He also made brilliant content. People swooned over the campaign logo, the clever and culturally relevant video content, and his ability to seemingly be everywhere on social media.

His policies, his media presence, and his personality led 21,000 people speaking more than dozen languages to volunteer for his campaign.

I know, I know, yard signs aren’t votes.

Mobilization over Favorability

This week’s episode of the show featured Anat Shenker-Osorio, who was truly focused on getting past the usual dependent variables: Does a candidate or message have high favorables? Does a candidate or message get vote preference?

Instead, she says we should be trying to figure out how to estimate mobilization.

If you included the potential for mobilization in your models, as it appears PPP did, you’d factor in those volunteers, and that social presence, and that community engagement, and that cultural momentum. You’d think about who is mobilized and who is demotivated. You’d wonder, whose base of voters are more likely to choose the couch?

Now, who knows. It’s entirely likely PPP got lucky.

But it seems like the thing they were trying to assess was: what kind of market maker do we think Zohran Mamdani is? And it turns out, he’s a market maker with a wider bid-ask spread than Cuomo had. The voters were there, the ideas were there. Someone just needed to connect the two.

This whole thing started with mobilization and whether it lives or dies will depend on mobilization too

Here is another measure of mobilization:

Another thing Anat and I talked about is the importance of people putting their bodies out into the world. She said, in our conversation, this:

“[T]he way that Democrats are gonna come around is when the movement, when ordinary, everyday people are out in the world. They're not gonna go first. They're not gonna go first. They are not leaders. Leaders go first... But the way to change Democrats is by changing ourselves.”

Right in this moment, the Roberts Court has given the Trump regime a blank check. They can do anything and it won’t be illegal. Today they took away the power of district courts to stop the executive branch from breaking the law. The MAGA Congress thinks people will just “get over it” when they take away health care access from millions. We have blown past constitutional crisis. The branches are no longer doing the Constitution, such as it was.

There’s a real opportunity here, then, in people standing up for the imputed values of the Constitution (really they’re thinking of the Declaration and the Emancipation Proclamation, and FDR and JFK, and the unions, and the Civil Rights movement, but I digress). In the Constitution, “the people” have rights, some of which come with responsibilities. We have duties that we ought to perform. We ought to vote, and we ought to pay our taxes, and we ought to defend the nation when it is attacked. But other than that, the Constitution was the instrument by which we constrained government power.

That’s over now. There are no constraints that the government will recognize as against itself.

What’s left, then, are those rights and their implicit duties. We can gather, and say what we think, and disagree with the government, and we can sue, and we can vote, too, for now. We can be civil society. We can put our bodies into the world and demand a change.

I know we think about the Constitution as laying out a tripartite system of government. I know we think about the press as the “fourth estate”.

But in any system that wants to call itself a democracy, the original estate must always just be… us.

I hate “the couch”. It might not be the couch. It might be the desk, the office canteen, the school library, the gym, the grocery store, the car, the nursery, the hospital. The Couch suggests laziness, when often it’s simply that people really can think of something they believe is a better use of their time, even if you disagree.