People Like Me

A democracy indicator, as good as any other.

After the 2016 election, I read somewhere that there was an extremely high correlation between agreeing with statements like “people like me don’t have any say about what the government does” or “public officials don’t care much what people like me think” and voting for Donald Trump.

I have a dim memory of writing about this at the time on some long defunct Medium blog, but now that the ANES data is out, I’m once again wondering how well those questions correlate with a variety of voting-related choices, chiefly: voting to complete the oligarchic, authoritarian project by voting MAGA, or choosing not to vote at all.

ANES asks a series of questions as part of a diagnostic meant to measure perceptions of “external political efficacy”.

These statements, introduced in the 1950s, originally included these four:

I don’t think public officials care what people like me think;

Voting is the only way that people like me can have any say about the way the government runs things;

People like me don’t have any say about what the government does; and

Sometimes government and politics seem so complicated that a person like me can’t really understand what’s going on.

Not all of these statements are still tested in the ANES, many are contested as to their power, accuracy, and cross-cultural validity. But ANES still includes statements 1 and 3 in their pre- and post-election surveys. And the general trend is bad. The vast, vast majority of people agree or strongly agree with these statements. The other questions in this section now are about whether politics are too complicated (in both a true/false version and a “how often they feel that way” version), and a version of the old question 4 about how well they feel they understand political issues.

The Decline

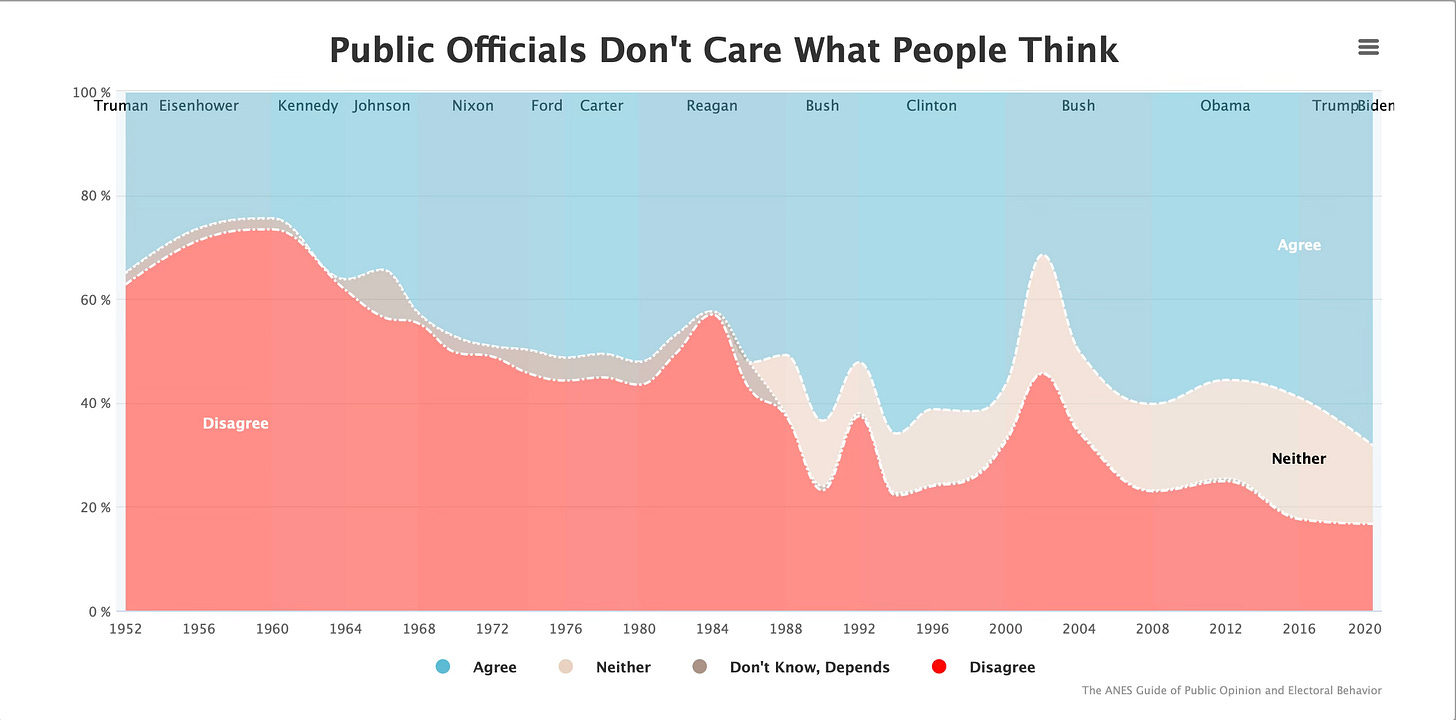

In 2020, 42% agreed somewhat, and 26% agreed strongly with the statement, “Public officials don’t care much what people like me think”. 38% agreed somewhat and nearly 24% agreed strongly with the statement, “People like me don’t have any say about what the government does.”

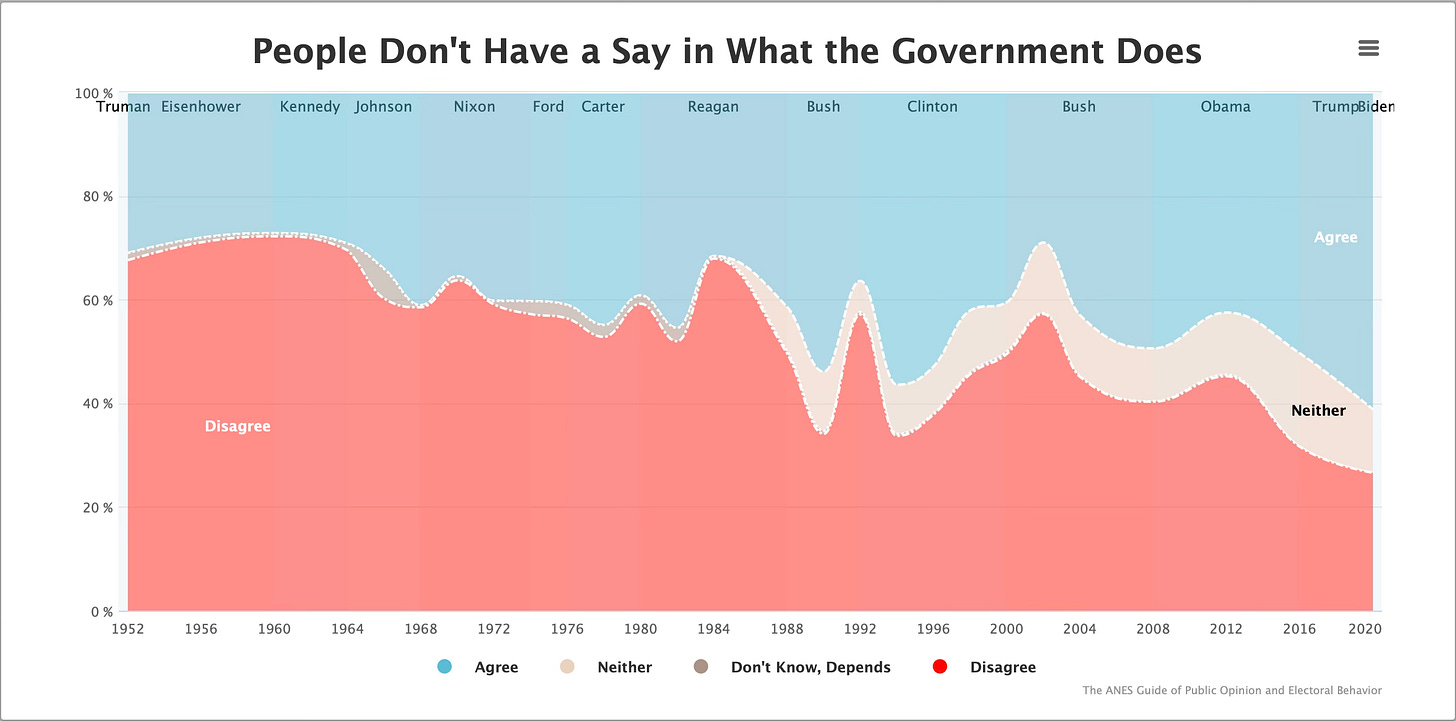

Here’s what the data looks like, plotted over time.

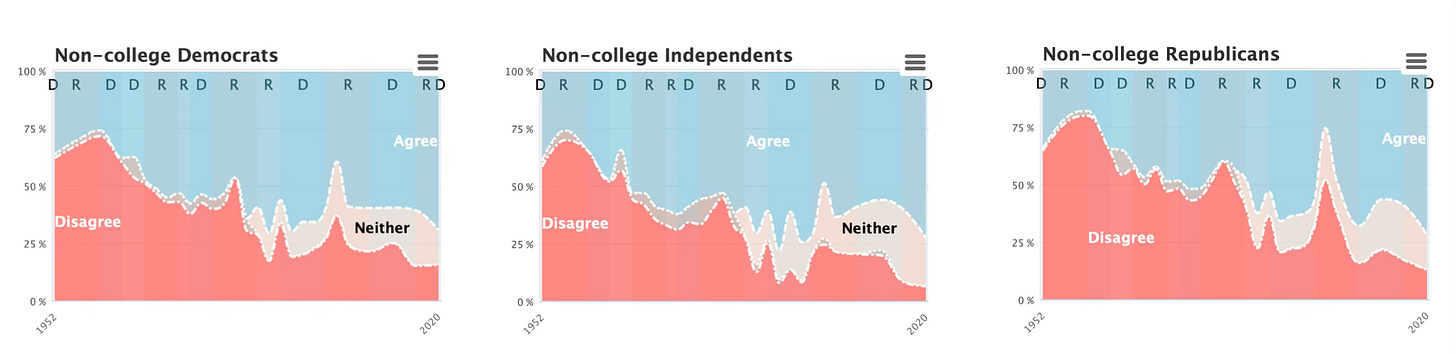

ANES has some pretty handy tools, so I looked at this data by educational attainment and party ID, just out of curiosity. Here’s non-college voters by party ID/lean.

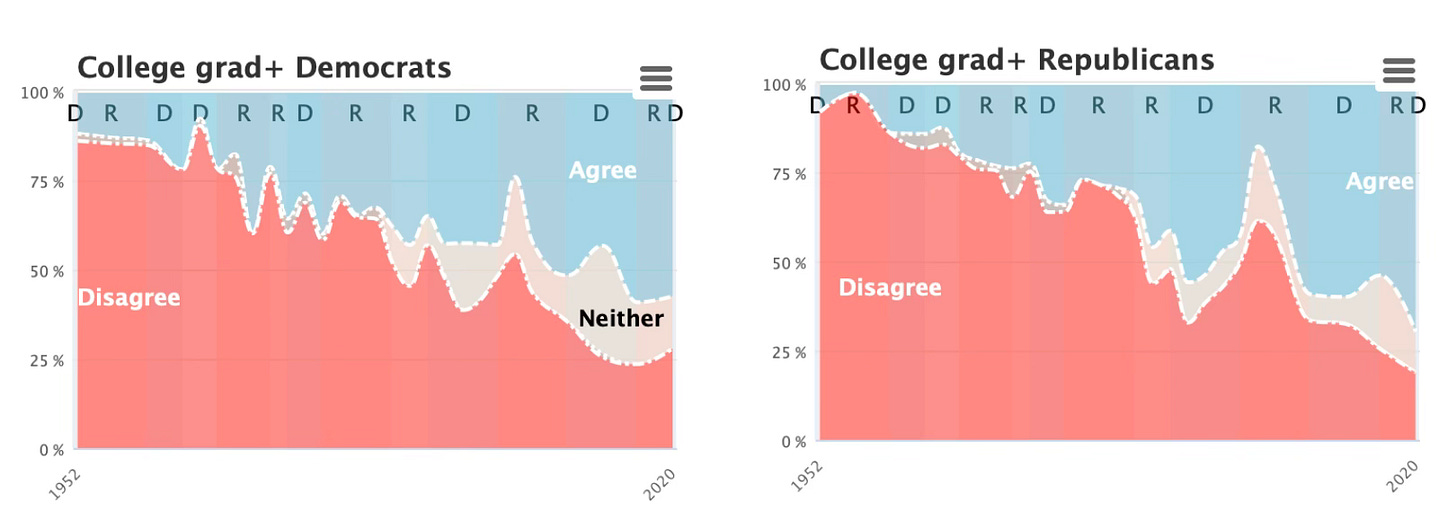

And college+ voters by party ID/lean (data for college grad+ Independents only goes back a few cycles for some reason, so I’ll leave that out for now).

Regardless of your party ID or education level, the sense that people like you have a say has generally declined over the years, but generally more steeply for self-identified Republicans, regardless of education level.

Now let’s look at whether you think public officials care what people like you think.

Here it is, just by party ID/lean.

This one’s interesting for a variety of reasons - everybody’s sense of this declines in the 90s, but it really declines for self-identified independents. And while the Democrats slope is a little less steep, it’s because Democrats started out less likely to think public officials cared much what they thought.

You can take a look through these visualizations, and you can do some cuts using Southern states/non-Southern states too. But regardless, these indicators of external efficacy have been worsening over time.

The Qual Beneath the Quant

Now, as someone whose research expertise is in qualitative methods, I have so many questions.

Who are ‘people like me’? What is the respondent imagining when they picture ‘people like me’? What are the shared characteristics that matter in this idea?

What would it mean to ‘have a say’? What form would ‘having a say’ take? How would you know if you had in fact, ‘had your say’?

In the context of ‘what the government does’ - what are they picturing? What government acts or responsibilities do they want a say in? What do they imagine is ‘what the government does’?

In the context of public officials not caring what they think, which public officials? How would they know if a public official cared what they think? What would that look like? How would they let a public official know what they think?

What are the consequences of government not giving them a say, or public officials not caring what they think — both for them as voters and citizens, and also for the government or those public officials?

First, let’s define some terms

For the purposes of this newsletter going forward, I want to interject here a set of definitions for terms I’m going to use for the foreseeable future to describe different groups of people:

The money class: If you earn most of your income from investments - stock dividends, interest, stock sales, trust funds, rent-seeking, etc. - and if the bulk of your net worth is investments in something other than your primary residence and a 401k, you are in the money class.

The working class: If you earn most of your income as a W-9 employee, or a 1099 contractor, providing work (services, labor) in exchange for a fee; or if you make and/or sell things to customers as your primary source of income, you are in the working class. You might be worth $2million on paper because of the current assessed value of your home, but if your income comes from a paycheck, or if you get paid in exchange for some kind of work, you’re working class just as much as the housing-insecure hourly wage earner.

And here’s why. The money class — some of whom have risen to the level of oligarchs — are part of a class with a lot of representation and collective power. They are intertwined with banks, hedge funds, venture capitalists, private equity funds, publicly traded companies, stock exchanges, and other providers of financial services. These organizations spend a lot of time, effort, and expertise on helping to create policy that is beneficial to them, and their customers.

The working class — some wealthier than others to be sure — are part of a class with little or no representation and collective power. Even the stratification of working classes — “upper middle class”, “middle class”, “lower middle class”, “the working poor”, “white collar” and “blue collar”, etc. — serves to deconsolidate this much larger group of people in society. Which is a shame.

Because the money class knows the answers to the questions I wrote above. They know exactly who is “like them”. They know exactly what “having a say” means. They know exactly what it looks like when public officials care what they think, and they know exactly what parts of what government does they want to influence.

And they think a lot about the consequences — both for them, and by them — of being left out.

So what if you’re, like, really rich?

I started thinking about this today listening to The Bulwark’s Tim Millerinterviewing Jason Calacanis, of the All In Podcast.

As Calacanis describes it, people like him are investors and “business builders”. They are capitalizers — the people who place bets/invest money in businesses in the hope that those businesses grow enough for their bets to pay out. He doesn’t call himself a gambler (another word for someone who places bets) — no, his money “builds businesses”.

Calacanis is quite explicit about what “having a say” means. It means being invited to the White House; it means having your calls returned; it means being invited to summits and parties. It means having conversations with members of the administration, that crucially, are never followed by investigations by the SEC. It means being invited to be the crypto czar or the unofficial DOGE administrator. It means getting to decide what the regulations and who the regulators should be.

When public officials care what they think, they get those invitations (never summonses!), and they get favorable regulatory and tax policies. When public officials care what they think, they get richer.

They want to influence the things government does that could make them richer or poorer — again, tax and regulation at the forefront, but depending on their investments, it might also be energy policy, foreign policy, national security policy, immigration policy and so on. These policy areas are secondary to the tax and regulation interests they hold, but they do have policy preferences, and because they are “business builders”, they feel they are qualified to have a say on anything that interests them. You know, like vibe coding, or vibe physics, we also have vibe governing.

The consequences of being left out are also clear. Snub them on an invitation and they will endorse and fund your political opponents. Regulate their businesses, and they will defy, sue, lobby, and overturn your regulations through the courts or the legislature or the ballot box. The consequences to them of being left out are equally clear: they won’t be as rich next year (and the year after that, etc.) as they want to be.

Here’s a section of the conversation Tim had with Jason that I found so revealing:

Jason: The contempt issue is partially the outward contempt and what they would say and their actions. So we talked on the last episode when you and I talked on October 15th about not inviting Elon to the EV summit.

Tim: I know people's feelings get hurt.

Jason: It's yeah super disrespectful and it matters, I think, to the business community because we take them at their word when they say we should ban billionaires or we should look into that guy which was Biden's big thing. Um we actually and when you see the Delaware courts…

Tim: Trump was just [ __ ] on the Intel CEO yesterday, calling him like a Chinese crypto, a Chinese asset or something. I mean, if we're talking about, oh, people being a little mean to business guys, it's not like Trump hasn't, doesn't do that.

Jason: The perception is, you know, if you wanted to talk to them, they weren't available to talk to you. Uh, and no amount of donations, lobbying, or even just, hey, I want to have a goodwill discussion were allowed. and and that socialist uh Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, now um Mandami, that whole group I think is how the business community, finance community, tech community started to look at the Democratic party. This was their biggest mistake because Clinton didn't feel this way. Obama didn't feel this way. This was like a kind of a new thing. And all the people I mentioned earlier, they all supported Obama. They all supported Clinton. So we were essentially as a business community um told you know need not apply, need not to be involved and we're just going to um make things difficult for you and there's no conversation and so yes you we will get into Trump's uh mercurial, you know, shaking of the snow globe of business is the way I look at it um and the impact that has. But net-net any business person you talk to, any CEO behind closed doors will say, ‘This is a much better situation for business right now.’

In Jason’s version of good (for business) government, he should be allowed to make donations in exchange for attention and favors, lobby for policy he wants, and be directly engaged in conversations with policy makers and regulators.

In his version of good (for business) government, any politician who might want to curtail those activities — activities often thought of by normal people as on a spectrum of corruption — are bad.

But they’re not just bad, they’re dangerous: “We take them at their word when they say we should ban billionaires.”

External political efficacy is achieved when you believe that public officials care what you think, and you have a say in how government is run. For some of us, when we don’t believe these things, we simply lose trust in government.

But when you’re rich enough, if you start to “lose trust” in government, the solution is simple: you buy yourself a new one.

And anybody who might want to crack down on that corruption/access — well they must be stopped.

P.S. That’s not Anarcho-Capitalism

So, the episode title in my podcast feed mentioned anarcho-capitalism. Here’s the quote from the transcript from Jason:

“So, I think we're between a socialist kleptocracy and anarcho-capitalism.”

I mean, wow.

To be honest, at first I wasn’t sure if he said “narco capitalism1”, and neither is the robot transcriptionist.

So what is anarcho-capitalism? Wikipedia’s definition is probably fine:

“Anarcho-capitalism (colloquially: ancap or an-cap) is a political philosophy and economic theory that advocates for the abolition of centralized states in favor of stateless societies, where systems of private property are enforced by private agencies.[3] Anarcho-capitalists argue that society can self-regulate and civilize through the voluntary exchange of goods and services. This would ideally result in a voluntary society[4][5][6][7] based on concepts such as the non-aggression principle, free markets, and self-ownership. In the absence of statute, private defence agencies and/or insurance companies would operate competitively in a market and fulfill the roles of courts and the police, similar to a state apparatus.

So… squint and you can see that this is something that Jason has definitely heard people talk about because there are echoes of “network states”, which the friends he invites over to Mountainhead are super into.

The degree to which we are “between a socialist kleptocracy and anarcho-capitalism” depends on where you’re sitting. Also, there ain’t nothing socialist about this kleptocracy.

If on the other hand, he did mean to say narco capitalism, I think, metaphorically, the case can be made. But in our case the “narco” - the illegal or addictive substance is probably, like, social media, LLMs and crypto.